Yesterday I finished Crime and Punishment. No spoilers, but there was definitely a crime. And some punishment. But that’s enough for today.

It’s 4th of July season here in the United States, and I can’t think of a more summer-y, more American topic than 1800s Russian literature.

So light your fireworks and bust out your grills.

And get ready for a blast of bitter cold and bitter characters.

Why do I like 1800s Russian literature?

To be honest, I’m new to these waters. My first real introduction was The Brothers Karamazov, which was one of my top books last year. Why was it one of my favorites?

At first it’s hard to say.

It was a difficult read, sometimes slow.

Every character has about four names that are used interchangeably. (Alexei Fyodorovich Karamazov aka Alyosha aka Alyoshechka etc).

Culturally, there were a lot of things I didn’t immediately understand.1

And most, if not all, of the characters were anxious, depressed, impoverished, stressed, hurt by people they loved, and cold. Very cold. Almost all of the time.

But despite all of that, I found myself loving it. And reading two more of Dostoevsky’s books this year.2 And reading this selection of Russian short stories. And planning to read Tolstoy’s War and Peace later.

So what’s the appeal? Why should you try? Here are:

3 reasons you might enjoy 1800s Russian literature, too

I’m not an expert. I’m very new. So these reasons might not hold true for all the Russian literature out there. But they’re what keeps bringing me back.

1. Irrationality in thought (& actions)

Humans aren’t rational. Humans aren’t consistent. We change our minds. We monologue. We get annoyed, we get excited, we get annoyed again. We get annoyed that we’re getting annoyed. We remember we’re cold. We say one thing and mean another. We take a walk and wish we hadn’t.

All of Dostoevsky’s work I’ve been reading is PEAK exploration of that weird part of our interior selves. Why do we do what we do? Why do we think what we think?

I’m not saying the characters are completely relatable, as in — “that’s exactly how I see the world!” — but the way they think, change their minds, think again, is relatable. Here’s a snippet of an interior monologue from Crime and Punishment.

“Shall I tell them or not? Ah…the devil! Besides, I’m tired; I wish I could lie or sit down somewhere soon! What’s most shameful is that it’s so stupid! But I spit on that, too. Pah, what stupid things come into one’s head…”

—Raskolnikov in Crime and Punishment, Part Two, Chapter 63

You might not think long monologues of people contradicting themselves would be your thing.

At first glance I didn’t think they’d be my thing, either.

But they grow on you.

2. Why do humans self-destruct?

Have you ever done something you know will be bad for you? Maybe you’re even thinking of it in the moment you do it. Maybe you don’t even want to do it. Maybe it’s not even fun.

But you do it anyway.

Why? Why would we do this?

I’ve never found any stories that address this strange behavior more than the three Dostoevsky books I’ve read lately. Each of them has at least one character who, in their own way, is stuck in a spiral, knows they’re stuck in a spiral, and is continually complicit in their own self-destructive behavior.

(Dmitri in TBK, Raskolnikov in C&P, and — to a much greater extent, actually — the narrator from Notes from Underground.)

I don’t like watching these characters fail, get up, and fail again. I’m not rooting against them.

It just makes me think.

Again, this phenomenon might not exist in every Russian story. It probably doesn’t. But it’s been recurring in my reading and I think it’s worth bringing up.

“What is to be done with the millions of facts that bear witness that men, consciously, that is fully understanding their real interests, have left them in the background and have rushed headlong on another path, to meet peril and danger, compelled to this course by nobody and by nothing, but, as it were, simply disliking the beaten track, and have obstinately, wilfully, struck out another difficult, absurd way, seeking it almost in the darkness.”

—Notes from Underground, Part One, Chapter 74

3. Is there hope, at all?

Guys, not to spoil anything.

But sometimes,

even when it’s sunny out and Popsicles are on sale and the hot dogs are on the grill,

life can still be really hard.

Hard in a thousand ways. Different for everybody. Everybody has something going on.

And stories that pretend otherwise fall flat.

One thing I love about these books I’ve been reading is that they don’t shy away from hardship. There is no sugarcoating.

There is physical hardship. There is emotional hardship. There is poverty and death and unfulfilled dreams and selfishness. Even in joy, there is hardship.

But even in the hardship, in the blizzard, there can be joy.

No, these stories don’t wrap up with “and then everything was all right!” There are real sadnesses, real consequences. (It’s called Crime and Punishment, not Crime and Peach Cobbler.)

No, they’re not Dandelion Wine or Little Women (or Crime and Punishment’s named twin, Pride and Prejudice).

But there’s something special about a book that shows all of humanity’s crap, all of our inconsistencies and flaws, all of the unfair things that happen to us and that we do to ourselves.

Because now we know what we’re dealing with.

And we can figure out what to do from there.

“I say this in case we become bad,” Alyosha went on, “but there’s no reason why we should become bad, is there, boys?

—Alyosha in The Brothers Karamazov, Epilogue, Chapter III.5

So where should you go from here?

This newsletter’s plenty long as it is. I’ll recommend the four 1800s Russian books I’ve read in the past year, and why you might like each of them. (Apologies in advance that I’m not offering a wider variety. Working on it.)

The Brothers Karamazov (Dostoevsky): A longer, epic read. My personal favorite of the lot, and (I think) the most hopeful. But be warned, long.6

Notes from Underground (Dostoevsky): The shortest, the most rambliest, the most depressing, probably. Do you want to hear an angry person who’s intentionally ruining his own life monologue at you for 150 pages? This is the book for you.

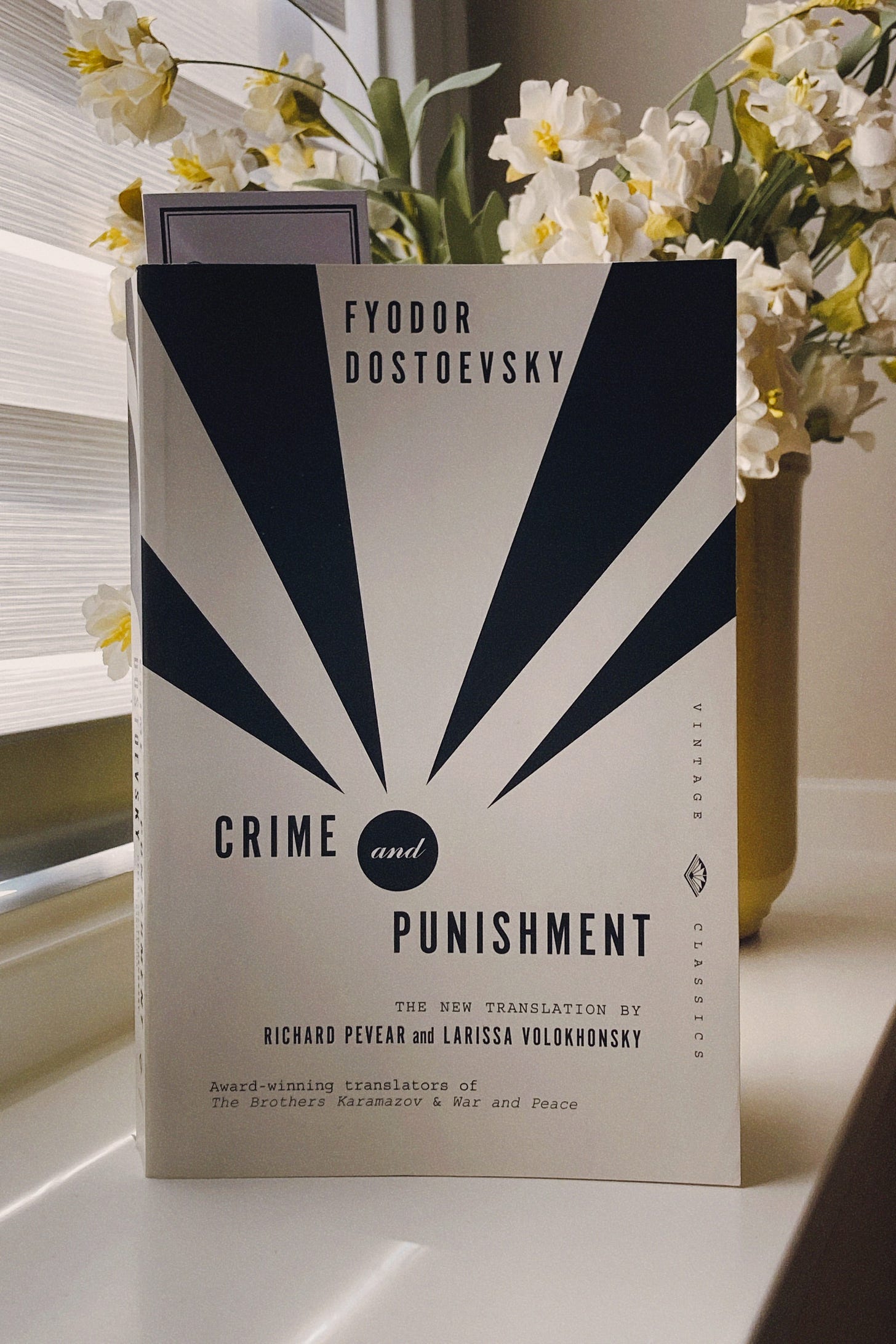

Crime and Punishment (Dostoevsky): I’ll be honest, this one was hard. If you’re a glutton for punishment (ha) then by all means tackle it. I loved it, there are some really fantastic parts to it, but is definitely not an easy read.

The fourth book is different and deserves its own section. And if you want an introduction to Russian lit, it really might be the book for you.

A Swim in the Pond in the Rain by George Saunders

So Saunders is actually not an 1800s Russian author.

He’s a very-much-alive author and literature professor at Syracuse. And A Swim in the Pond in the Rain is a study on writing, based on seven Russian short stories.7

(The book’s subtitle is In Which Four Russians Give a Master Class on Writing, Reading, and Life.)

The stories in the book are by Chekov, Gogol, Turgenev, and Tolstoy. Each story is presented in its entirety. Then Saunders explains his thoughts on why the story works.

If you’re at all interested in writing, I can’t recommend this book more highly.

If you’re not particularly interested in writing, I still recommend this book.

The seven stories are really beautiful, and Saunders’ essays illuminate them even more beautifully. (My favorite is The Singers by Turgenev.)

You might think having a literature professor explain a story would be boring and academic and bleh.

It’s not. I loved the whole experience.

So, if you’d like to dip your toes into old Russian books, but don’t want to sit through something super dense, consider A Swim.

And that’s ACTUALLY the end.

If you end up reading any of these, or have another Russian book I should read, say hey to me here!

Best,

Tim

P.S. Here are some YouTube videos on books and creativity I’ve posted since the last newsletter!

The footnotes at the end of the book were, however, very helpful. More helpful than this footnote, probably.

I mentioned Crime and Punishment earlier. The other one is Notes from Underground.

Translation by Richard : and Larissa Volokhonsky, 1992.

Translation by Constance Garnett, 1915.

Translation by Constance Garnett, 1912.

This illustration (& the rest of the black and white illustrations in this newsletter) were taken from the Constance Garnett translation of The Brothers Karamazov, published by Random House.

And I actually briefly recommended this book in the April edition of this newsletter. But I wanted to give it the spotlight here.

I read War and Peace a couple years ago and it turned my grumpy and irritable personality around so needless to say, it's special to me. I can't wait to hear what you have to say about it.

I am a big fan of Russian lit but never really figured out why. This article really hits the mark I think.

Also, read The Idiot by Dostoevsky. Your third point about hope immediately made me think of the poor Prince Myshkin.